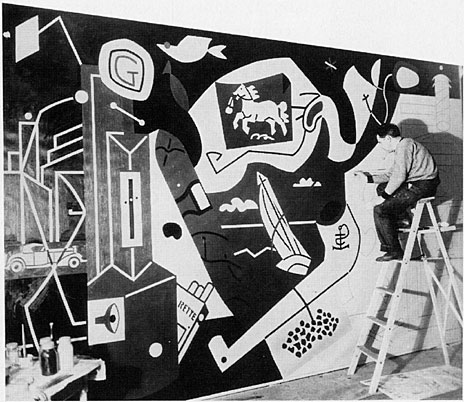

Stuart Davis at work on Men Without Women

This essay describes how the composition of Picasso's "Guernica" (1937) resembles Stuart Davis' 1932 mural for Radio City Music Hall.

(From Art and Antiques magazine, December 1989)

By Karen Sullivan and Delores McBroome

"When I am shown a portfolio of old drawings," Picasso said, "I have no qualms about taking anything I want from them." Such statements have spawned a sort of subgenre of art history devoted to discovering the various influences on the Spanish master's art. Much has been written about his 1937 mural Guernica; three new books about it appeared this year alone. But none of the scores of books and articles published so far even mentions a painting that appears to have been a major compositional source: Men Without Women by the pioneer of American cubism, Stuart Davis.

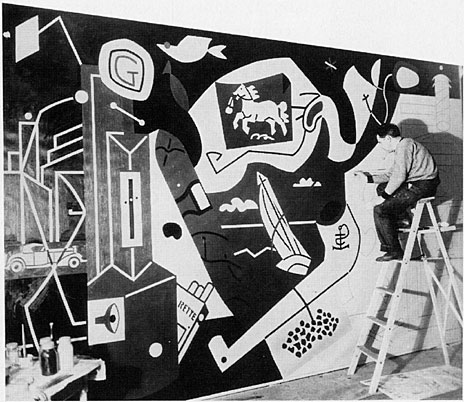

Stuart Davis at work on Men Without Women

While looking through the catalogue of a Davis exhibition, we noticed that his Men Without Woman bears a striking resemblance to Guernica. At first we assumed that Davis borrowed his composition from Picasso's painting, but on checking the dates of the two murals, we found that Davis completed Men Without Women in 1932, five years before Picasso painted Guernica. The similarities between Picasso's and Davis's murals are undeniable: their complex but harmonious organization of forms, their distribution of light and dark, even specific shapes are nearly indentical. But how did Picasso, who had never visited America, see Men Without Women? The unveiling of Davis's mural-commissioned for the Men's Lounge of Radio City Music Hall-was a widely publicized event, and photographs of the painting appeared in many newspapers and magazines. We know Picasso was a voracious collector of art clippings and objects; his houses were crammed with drawings, paintings, and books. Gertrude Stein regularly saved clippings for him including the Sunday issue of the New York Times. (Davis himself frequently visited Stein's Paris house to view her Picassos.) Since Men Without Women was an important modern work (the title was first used by Ernest Hemingway, another Stein regular), it's likely there was a photograph of it in Picasso's collection. And, given his visual memory, he need only have glanced at the picture once or twice for it to leave an indelible impression. It's entirely possible that Picasso used it as a model for Guernica. But if so, why has no one noticed it until now?

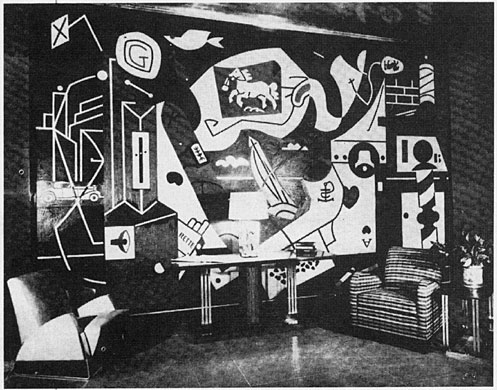

Picasso's 1935 etching "Minotauromachy"

Perhaps because scholars in search of sources for Guernica have been familiar with Davis's work only in living color and, as Picasso himself said, the color in a picture can be a distraction. It is only in black-and-white photographs (as Picasso would have seen the mural) that its correspondence to Picasso's painting becomes clear. In fact, it appears that elements in Guernica came from the specific photograph of Men Without Women, shown on page 44, that we found in the January 1933 issue of Arts and Decoration magazine. Picasso's ravenous eye absorbed not only Davis's mural but the flash reflection on the ceiling and the chairs in the foreground, transforming them into flames and the hand and foot that anchor Guernica.

When Davis first saw Guernica, he called it "one of the greatest formal syntheses in the history of art painting." Perhaps he admired the composition because it was the way he would have done it (or had done it). But Davis wouldn't have been comfortable creating a painting with such an overt message. "Art knocks you out on a physical level, without showing you its Passport," Davis said. "The impact of Guernica rests on that basis." Though Davis was a WPA artist, he remained primarily interested in aesthetic concerns. "An art of real order doesn't say 'Workers of the world unite,'" he once said. "It doesn't say 'Pasteur's theory had many benefical results for the human race,' and it doesn't say 'Buy Camel cigarettes'; it merely says 'Look, here is a unique confiruration in color-space.'"

Picasso was commissioned in January 1937 by the Spanish government-in-exile to create a mural depicting the horrors of the Spanish Civil War for the Paris International Exposition that summer. On April 28, news of the brutal bombing of the Spanish town Guernica reached him and within two days Picasso was galvanized into action. He started sketching studies for the mural on May 1, and in ten days was drawing forms on the eleven-by-twenty-five-foot mural surface.

Picasso may have produced Guernica very quickly, but the principal characters in the mural-the bull, the horse, the little girl, the weeping mother, and the fallen soldier- were motifs he had used in his work for years. His painting of the atrocity is essentially a reworking of intensely personal themes that appeared over and over in drawings and prints like Minotauromachy. But while the characters were familiar to Picasso, never had he combined quite so many of them in one work, and never with the complexity of Guernica. It's blend of realism and abstraction is unlike Picasso's seminal cubist canvases, but very much like what Davis called his "homegrown, personal brand of Americanized cubism": the style of Men Without Women. Picasso's memory of Davis's masterful composition seems to have provided the blueprint for Guernica.

Details from this photo of Davis's 1932 mural in its setting...

turn up throughout Picasso's 1937 mural Guernica, which marked a departure in style for the artist.

Picasso, who so often said "We must pick out what is good for us when we find it," never specified what he had picked and from whom. To what extent was this European masterpiece shaped by an American artist? The closest thing to a definitive answer can only be found in a comparison of the two paintings. There are at least eight elements from Davis's mural which appear in Guernica: both have white horses in the center of their composition; Davis's X-shaped sign in the upper left looks much like the bull's tail in the same spot in Guernica; Davis's symbol "G" (for gasoline) is very close to Picasso's bull head and horns; Davis's sailboat looks like the slot-shaped wound in Picasso's horse; Davis's bird in the upper left may have become the central light bulb in Guernica; Davis's diagonally pointing cigarettes suggest a hand form in Guernica in about the same place and direction; the focal point of Davis's mural, a headlike form veering toward the center-left, is similar to Picasso's light-bearer in value, proportion, location, and direction. Components Picasso may have appropriated from this specific lounge photo, besides the aforementioned flames and feet, include: the tile floor and the interior ceiling, part of a woman's garment on the right of Guernica that echoes the stripes on the chair on the right in the photo, a gray light shaft behind Picasso's bull resembling a reflection off the wall in the photo, and the legs and body of the horse that echo the lines of the table in the center of the lounge photo.

Guernica has been hailed as the last masterpiece of painting to be provoked by a political catastrophe. Could Stuart Davis's formally oriented mural have paved the way for Picasso to achieve his emotion-laden masterpiece? We may never be certain, but the master's cavalier remarks keep prodding us to look for new sources: "The laws of composition are never new," he said. "They are always someone else's."

Karen Sullivan is an artist and former art instructor, and resides in Eureka, California. Delores McBroome is a historian at Humboldt State University, Arcata, California.